Bladder Cancer

In the UK there are around 10,000 new cases of bladder cancer each year. The reason that people develop bladder cancer is becoming better understood. People with certain risk factors appear to be more likely than others to develop bladder cancer.Men get bladder cancer much more commonly than women. It is rare for anyone under the age of 50 to get it but it becomes more common as people get older.

What causes bladder cancer?

Cigarette smoking is a strong risk factor for the development of bladder cancer. The risk of developing bladder cancer is related to how many cigarettes and for how long a person has smoked. Bladder cancers can develop many years after a person has stopped smoking. Other important risk factors include exposure to certain chemicals such as aniline dyes that were previously used in dye factories and various chemical industries. Previous cancer treatment with cyclophosphamide or pelvic radiotherapy also increases the risk of developing bladder cancer.

What are the symptoms of bladder cancer?

The most common symptom associated with bladder cancer is the presence of blood in the urine (haematuria). Blood in the urine can be visible to the naked eye or detected only with the aid of a urine dipstick test or microscope (microscopic haematuria). Other symptoms associated with bladder cancer include recurrent urinary tract infections, pain on passing urine, passing urine more frequently, urinary urgency or a weak urine flow.

What investigations are required?

People presenting with blood in their urine or symptoms suggestive of bladder cancer are often investigated with a cystoscopy. This is a telescope examination of the inside of the bladder, prostate (in men) and urethra. This investigation is conventionally performed using a special telescope called a flexible cystoscope under local anaesthetic. Bladder cancer can usually be seen clearly using this technique. Urine is sometimes additionally sent for urine cytology testing. This is an investigation where the urine is examined under a microscope to look for any abnormal cancerous cells.

Patients undergoing investigation for blood in the urine or suspected bladder routinely have imaging of their kidneys and ureters. Patients with visible haematuria have a CT scan with contrast (CT urogram) whilst those with microscopic haematuria are evaluated with a non contrast CTKUB.

Are there different types of bladder cancer?

Bladder cancers are given two “scores”: a grade and a stage. Bladder tumours are graded according to how abnormal the cells look under the microscope, from Grade 1 (least abnormal) to grade 3 (most abnormal). In 2004 this system was revised and the tumours are graded:

- Urothelial papilloma

- PUNLMP (papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential)

- low grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

- high grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

You may see both grades reported.

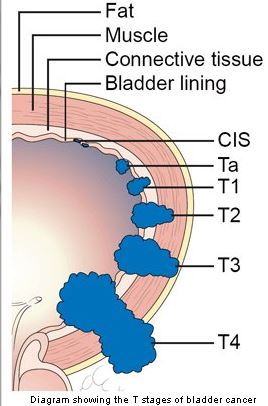

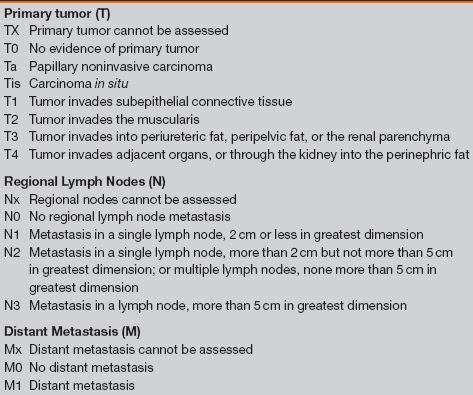

The tumours are staged according to the TNM staging system. The T stage for bladder cancer indicated how far the cancer has spread locally. The N stage indicates if it has spread to lymph nodes, and the M stage describes whether it has developed distant spread or metastases.

The tumours are staged according to the TNM staging system. The T stage for bladder cancer indicated how far the cancer has spread locally. The N stage indicates if it has spread to lymph nodes, and the M stage describes whether it has developed distant spread or metastases.

What is the difference between non-muscle invasive and muscle invasive bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer is described a superficial if it is Ta or T1, and muscle invasive if it is T2 or greater. Around 80% of bladder cancers are superficial at diagnosis.

These two types of cancer behave and are treated differently. Most Ta tumors are low grade, and most do not progress to invade the bladder muscle. Stage T1 tumors are much more likely to become muscle invasive. Stage Ta tumors often recur after treatment but they tend to recur with the same stage and grade.

What is carcinoma in situ (Cis)

The Tis stage classification is reserved for a type of high-grade cancer called carcinoma in situ (CIS). This is a very aggressive but superficial growth in the bladder, which can progress to become muscle invasive. It is often treated with BCG instillation into the bladder (intravesical treatment with BCG).

How is superficial bladder cancer treated?

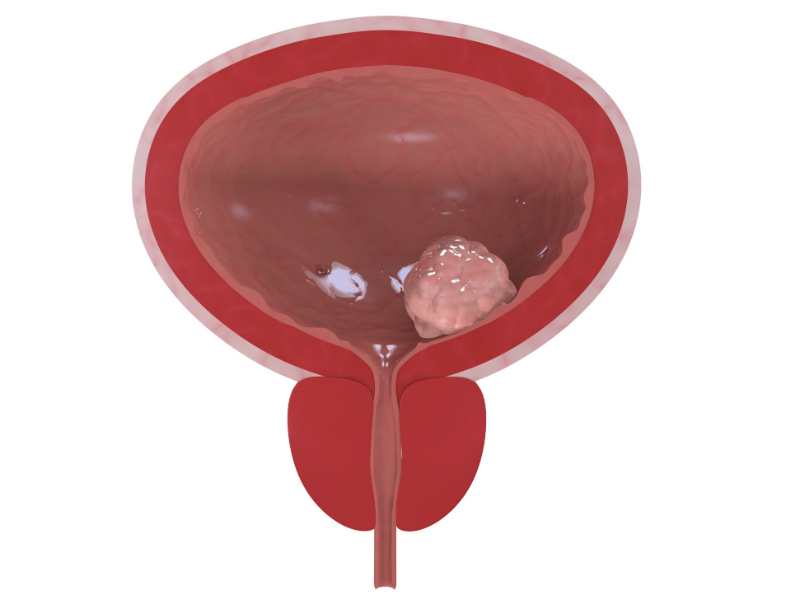

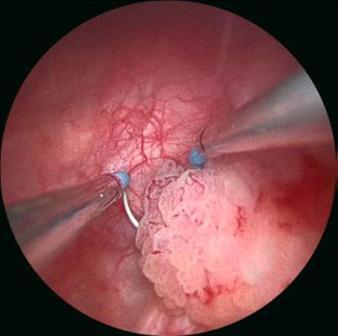

If a bladder cancer is seen during a flexible cystoscopy or CT scan the next step in the treatment pathway is to have a TURBT (Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour). In this operation the surgeon uses an operating telescope to remove the tumour from the inside of the bladder. The operation needs to be performed under either general or spinal anaesthetic and usually involves an overnight stay. In most cases the tumour can be completely removed during the procedure.

If a bladder cancer is seen during a flexible cystoscopy or CT scan the next step in the treatment pathway is to have a TURBT (Transurethral Resection of Bladder Tumour). In this operation the surgeon uses an operating telescope to remove the tumour from the inside of the bladder. The operation needs to be performed under either general or spinal anaesthetic and usually involves an overnight stay. In most cases the tumour can be completely removed during the procedure.

Once the tumour has been removed the cancer cells are analysed under the microscope by a pathologist. The key factor that determines further treatment requirements is the stage of the bladder cancer. Cancers that do not involve the muscle layer of the bladder are termed non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (Stage Ta & T1). These tumours can come back within the bladder despite a successful initial TURBT. Chemotherapy can be given into the bladder to reduce the chances of new bladder cancers forming or progressing to muscle invasive disease. The two most commonly used agents are Mitomycin C and BCG. Patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancers need to have regular inspections of the bladder to ensure that new tumours do not go undiagnosed. Any new tumours can be managed with repeat TURBTs.

How is muscle invasive bladder cancer treated?

For muscle invasive disease, cystectomy (surgical removal of the bladder) may be recommended. This operation may also be used for patients with CIS or high-grade T1 cancers that have persisted or recurred after initial intravesical treatment. There is a significant risk that the cancer may become muscle invasive in such cases, and some patients may want to consider cystectomy as a first choice of treatment. During a cystectomy, the bladder is removed, and then the urine is usually drained into a small segment of bowel and then bought out to drain onto the anterior abdominal wall (ileal conduit). In some cases, a new bladder can be formed out of small bowel, so that the patient can pass urine again normally.

Alternatively for less fit patients external beam radiotherapy might be recommended.

What is intravesical chemotherapy?

Following removal of your bladder tumour, intravesical chemotherapy or intravesical immunotherapy may be used to try to prevent tumour recurrences. Intravesical means “within the bladder”. These therapeutic agents are put directly into the bladder through a catheter in the urethra, are retained for one hour and are then urinated out.

The chief intravesical agents currently used are mitomycin C and bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). BCG is a live, but weakened, vaccine strain of bovine tuberculosis and it is now one of the most effective agents for treating bladder cancer and especially for treating CIS.

These agents are used because we know that they help to prevent tumour recurrence, and while mitomycin C (MMC) does not prevent the rate of progression (the chance of the tumour becoming more invasive), there is some evidence that BCG may.

Each agents produces irritative side effects such as frequent urination (up to 40 % for MMC, 60% for BCG), painful urination (70% and 30%). In addition, BCG therapy carries a 20% percent risk of flu-like symptoms and a small risk (4 percent) of generalised infection. There is a chance of skin rash with MMC (up to 15%).