Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer has become the most common cancer in men and is the second most common cause of male cancer deaths, after lung cancer. It is different from most cancers in that a significant proportion of men, particularly older men with a shorter life expectancy, have a very slow growing form of this cancer, meaning that it is unlikely to cause symptoms or progress beyond the prostate gland during their lifetime. Sometimes in younger men the cancer can be small, slow growing and present only a limited risk to the patient. Clinically important prostate cancers can be defined as those that threaten the well-being or life span of a man.

What are the symptoms of prostate cancer?

Often prostate cancer does not produce any symptoms, or it may produce symptoms similar to benign enlargement of the prostate, BPH. These include:

- difficulty in starting to pass urine

- poor flow of the urinary stream

- dribbling at the end of the stream

- the feeling the need to pass urine frequently, including at night,

- an urgent need to rush to pass urine, occasionally without any warning

- passing blood in urine

Often patients are diagnosed with prostate cancer after they are found to have a raised PSA blood test, or because they have an abnormal feeling prostate. However, PSA test is not entirely accurate. There is no real safe lower limit. Even in men with “normal” levels of PSA (less than 3 to 4 ng/ml depending on your age) around 15% may have small prostate cancers. Conversely, the PSA level may be increased by conditions other than the presence prostate cancer, such as BPH, urinary tract infection or prostatitis (infection in the prostate).

How is prostate cancer diagnosed?

Often prostate cancer does not produce any symptoms, or it may produce symptoms similar to benign enlargement of the prostate, BPH. These include:

- difficulty in starting to pass urine

- poor flow of the urinary stream

- dribbling at the end of the stream

- the feeling the need to pass urine frequently, including at night,

- an urgent need to rush to pass urine, occasionally without any warning

- passing blood in urine

Often patients are diagnosed with prostate cancer after they are found to have a raised PSA blood test, or because they have an abnormal feeling prostate. However, PSA test is not entirely accurate. There is no real safe lower limit. Even in men with “normal” levels of PSA (less than 3 to 4 ng/ml depending on your age) around 15% may have small prostate cancers. Conversely, the PSA level may be increased by conditions other than the presence prostate cancer, such as BPH, urinary tract infection or prostatitis (infection in the prostate).

How is prostate cancer diagnosed?

If the tumour in the prostate is large enough to be felt, your doctor may be able to examine it. With a gloved and lubricated finger, your doctor feels the prostate and surrounding tissues from the rectum. Hard or lumpy areas may suggest the presence of one or more tumours. Your doctor may also be able to tell whether it’s likely that the tumour has grown outside the prostate.

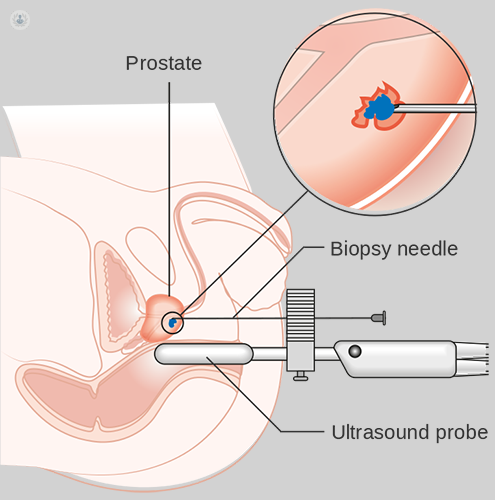

Men will almost always need to undergo an MRI and a transrectal prostate biopsy or a transperineal prostate biopsy in order to establish the diagnosis of prostate cancer.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging involves a strong magnet linked to a computer is used to make detailed pictures of your lower abdomen. An MRI is increasingly good enough to show where the cancer is in the prostate and tell whether it has spread to lymph nodes or other areas. Sometimes contrast material is used to make abnormal areas show up more clearly on the picture. We can use this information to guide the biopsy.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging involves a strong magnet linked to a computer is used to make detailed pictures of your lower abdomen. An MRI is increasingly good enough to show where the cancer is in the prostate and tell whether it has spread to lymph nodes or other areas. Sometimes contrast material is used to make abnormal areas show up more clearly on the picture. We can use this information to guide the biopsy.

Local Anaesthetic Transperineal (LATP) prostate biopsy

Oxford was one of the first places in the UK to have the expertise to offer this under local anaesthetic using the “Precision Point” device so please discuss this with your urologist.

This is a procedure to rule out the presence of cancer. It is typically performed if the prostate is suspicious from PSA testing / rectal examination / MRI scan results. An ultrasound probe is inserted into the rectum (back passage) and the prostate is imaged and measured. Then, under local anesthesia, multiple targeted cores from different locations in the prostate are taken and sent for analysis. Patients are given antibiotics before and after the procedure to reduce the risk of infection. Patients may experience some blood in the urine and in the ejaculate for up to six weeks following the procedure.

Mr Leslie and Prof Lamb were investigators on Oxford’s TRANSLATE Trial which was published in the Lancet in 2025. This was a UK randomised trial comparing transperineal biopsy under local anaesthetic (LATP) to the traditional transrectal (TRUS) biopsy in the detection of prostate cancer. It is an important trial which should have an impact internationally for men having investigations for prostate cancer.

How is prostate cancer graded (Gleason grade)?

The prostate tissue that was removed during the biopsy procedure can be used in lab tests. The pathologist studies prostate tissue samples under a microscope to determine the grade of the tumour. The grade tells how different the tumour tissue is from normal prostate tissue.

Tumours with higher grades tend to grow faster than those with lower grades. They are also more likely to spread. Doctors use tumour grade along with your age, overall health and other factors to suggest treatment options. The most commonly used system for grading prostate cancer is the Gleason score. Gleason scores range from 6 to 10.

To come up with the Gleason score, the pathologist looks at the patterns of cells in the prostate tissue samples. The most common pattern of cells is given a grade of 1 (most like normal prostate tissue) to 5 (most abnormal). If there is a second most common pattern, the pathologist gives it a grade of 1 to 5 and then adds the grades for the two most common patterns together to make the Gleason score (e.g.3 + 4 = 7). If only one pattern is seen, the pathologist counts it twice (5 + 5 = 10).

A high Gleason score (such as 10) means a high-grade prostate tumor. High-grade tumors are more likely than low-grade tumors to grow quickly and spread.

What is risk stratification?

With the information from the PSA, digital rectal examination and the biopsy results the level of risk of the prostate cancer can be assessed.

Treatment options

Men with prostate cancer have many treatment options. Treatment options include:

You may receive more than one type of treatment. The treatment that’s optimal for one man may not be optimal for another. The treatment that’s right for you depends mainly on:

- Your general health

- Your age

- Gleason score (grade) of the tumour

- Stage of prostate cancer

- Your symptoms